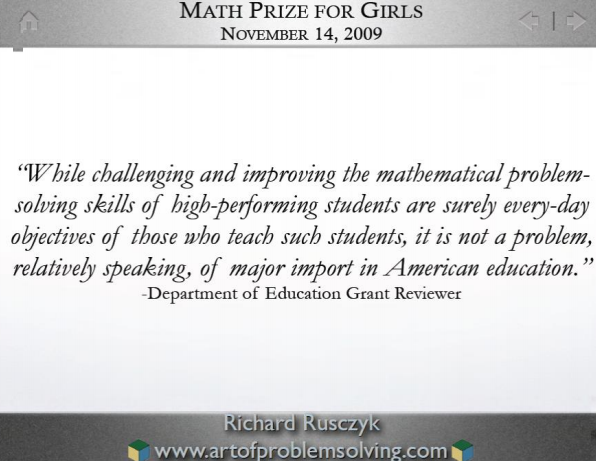

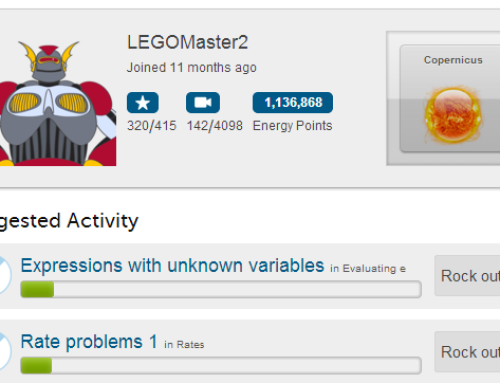

Wowsers! (Read the graphic above.)

All my math students (and their parents!) whine that the questions I give them are too hard….that they can’t do them.

I fire back, “I’m not hard….your school teachers are just TOO EASY.”

Most any adult will tell you that they learned the most in life when they were thrown into the fire. They learned and grew the most only when they were dealt new, daunting tasks – ones that positively scared them.

I’d like you to chew on some of these quotes from a *hard math advocate* who really gets it:

In the standard curriculum, the problems are just way too easy. Your children will zip through them really quickly. They’re not challenged. They never learn how to confront very difficult problems. Part of the problem also is that they develop a perfectionist streak. How many of your children are perfectionists, and it drives them nuts when they don’t get one hundred percent? They have to get over that. We don’t want them to get over that by slacking off. We want them to get over that by being presented with more meaningful challenges, because if you’re always getting a hundred percent on everything, you are not learning efficiently enough. You’re not learning as fast as you can and you’re not learning how to do things you haven’t seen before. What happens is just what we saw with my classmate. If the first time they can’t do something is college, they get so used to just being able to do everything because they’re “smart,” that once they can’t do something, they figure, “I’ve hit the wall. I can’t do this anymore. I’m quitting.” That’s another thing that the tyranny of 100% encourages in students. It encourages them to think, “I can do all this because I am so smart,” and once you can’t do it, then you’re done…

Also, if you use a lot of drill and kill, for students who are really curious and energetic and interested in the subject, doing the same thing over and over again is boring. But, even worse than being boring, it’s counterproductive. When you are drilling the same thing over and over into a student, you are programming them. You are making them become a computer and the problem is that we already have computers, and anything they can do, they can do better than we can. That gap between them and us will only get bigger. If you are setting a student up to be a computer, to compete with computers, you are setting them up to fail, because they can’t compete with computers.

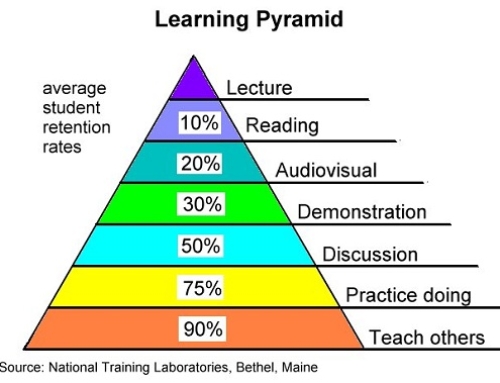

The last, and probably the most important, is that the lesson structure is backwards. Your typical class is, “I’ll show you how to do this trick. Here’s the trick. I’ll do it again. I’ll do it again. You repeat.” That’s the typical structure of a textbook, “Here’s an example. Follow. You do it.” That’s exactly backwards. That’s not how I learned mathematics. I learned math by seeing lots of problems and then figuring out what the lesson should have been. I figured out what the lesson was from working on all these problems and synthesizing it, making the ideas mine, instead of being something to copy. While doing that, I learned how to solve problems I had never seen before and that’s the key skill. More important than any single bit of mathematics they’ll learn is how to handle a problem that they’ve never seen before because that’s a transferrable skill. We can take this into law, medicine, economics, and any of the sciences and computer science. We can take that anywhere.

AHA!

Yes life is filled with hard problems. Problems we need to solve or confront without any a priori guidance. Problems that require intellectual perseverance.

You can read Richard’s whole speech here.

The graphic I have above is from his speech. Above average parents of above average children should take heed.

Leave A Comment